Below is a sample of the emails you can expect to receive when signed up to Nature Photographers Network.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Sarah Marino

Contributor

June 13 |

Originally published at: https://naturephotographers.network/articles/lessons-for-photographing-plants-using-shallow-depth-of-field/

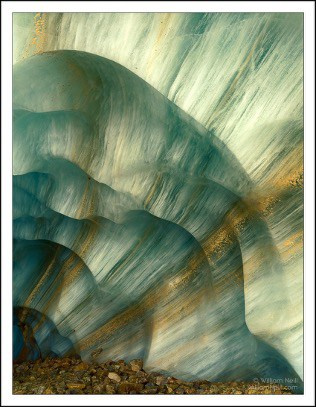

Photographing small subjects opens up a world of opportunity for nature photographers. By seeking out nature’s details, a photographer can explore a world of plants, patterns, textures, and abstract subjects that are often overlooked or seen in a less interesting way by the human eye. In this article, we will discuss one way of photographing small scenes: using shallow depth of field to render only a small part of your subject in focus. This article focuses on plants and leaves but you can use these lessons on any small subject you encounter in nature.

For many landscape photographers, embracing shallow depth of field and the out of focus elements that come with it can be a major shift in mentality. When photographing small subjects like plants or flowers, shallow depth of field can often transform a subject from the literal to the abstract. Generally, using greater depth of field renders a subject more literally with all of its details more obvious to the viewer. Shallow depth of field, on the other hand, often lends a more simple, dreamy, and abstract quality to a photo. Instead of photographing petals or stems or leaves, you are photographing lines and shapes. Additionally, the abstract renditions that can emerge make shallow depth of field an excellent simplifying technique when photographing a chaotic subject.

The subject of the photo below is an organ pipe cactus. I leaned in very close to a curving branch and selected a set of healthy cactus thorns, focusing on one very small section of the overall plant. By using shallow depth of field (here, an aperture of f/2.8), I was able to significantly soften the feel of the thorns and capture a more gentle portrait of this beautiful plant. The background, more of the cactus in soft even light, is far behind my subject which helps render the background nicely out of focus.

A wide aperture, like f/2.8 or f/4, helps pleasantly blur some of the details and leave just a slice of your subject in focus. This is the key to achieving the look of most of the photos you see in this article. In most cases, I set my camera to aperture priority, set the aperture for f/2.8 or f/4, and then get to work. If the background is far behind your subject, you can also use apertures closer to f/8 and still achieve the look associated with shallow depth of field while getting more of your subject in focus – for example, the aspen leaves below. Since each situation is different, it can be helpful to experiment with different apertures to see which option you like best given the specific qualities of your subject and background.

For this type of photography, I get quite close to the subject, often only inches away. For photos that require more precision, I set up a tripod, use manual focus, and experiment with small changes until I find the composition I like the most. This approach works best if you have a lot of room to work, are photographing a sturdy subject (like a cactus), or are working with no wind. If those conditions are not present, I hand-hold my camera, set the aperture for f/2.8 or f/4, and boost the ISO to get a faster shutter speed (at least 1/100 of a second if I am using a 100mm macro lens). I typically manually focus in this case as well, relying on my eye to determine if my intended subject is in focus (I sometimes also use a focus indicator in my viewfinder but find that I prefer to rely on my eye).

This latter approach allows me to freely move back and forth to experiment with small changes in position and focus since both of those choices can make a big difference in terms of the final result. When working with small subjects and rendering them with shallow depth of field, the tiniest changes in the focus point can entirely change the look and feel of a photo and I find it easiest to experiment without a tripod in these instances. If I need to use a tripod due to low light, I will often experiment with my camera off the tripod first to see what works best and then set up the tripod to finish the photo.

I created most of the photos in this article using a 100mm macro lens, a helpful but not essential tool. I use the Canon 100mm L f/2.8 lens but a basic macro lens or moderate telephoto lens from any manufacturer can work (the shorter the minimum focusing distance, the better; if you want to experiment with handholding your camera, a lighter lens is better). In addition to my macro lens, I have used a 24-105mm mid-range telephoto, 70-200mm f/4 telephoto lens, and a 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6 lens to create these kinds of photos. Thus, if you do not already have a macro lens, give your other lenses a try as you will likely get some good results with some practice, especially with larger plants and leaves in which a short focusing distance is not quite as important.

When using shallow depth of field, it is essential to experiment with varying focus points as doing so can have a big impact on the final result. Instead of trying to decide what I like best while out photographing, I take a lot of photos of the same subject using a lot of different focus points and different perspectives so I can decide which approach worked best after I get home and can see the photos at a larger size.

We can consider the example photos of the hedgehog cactus above. The two photos are of the same cactus but the focus point and direction makes a big difference in the final result. For the photo on the left, I focused on the cactus points, leaving the flowers out of focus. The flowers add a pop of color but are rendered as abstract forms. In the photo on the right, I moved to a different angle on the plant and focused on the flower blooms. Although the photo still has a bit of an abstract feel, it is a much more literal interpretation of this plant.

I photographed this subject in a few different ways and with different focus points – the cactus points in the very front, the cactus points in the very back, the cactus points at various places in between, with the flowers in focus, with the flowers out of focus, and with the focus point on the cactus plant rather than the tines or flowers. This kind of experimentation is typical when I photograph plants in this way, as I never know which renditions will look the best when I first choose my subject. This approach, especially when hand-holding my camera, produces a lot of failures but the failures are necessary to get to the successes.

When using shallow depth of field, another important consideration is your background. With a wide open aperture like f/2.8, only a small slice of your scene will be in focus. If other elements of your scene are just beyond the focus point, they will be out of focus but still recognizable and sometimes distracting. If the background elements are at a greater distance behind your subject, they will be rendered in an often more pleasing way – a soft, more even set of abstract shapes that do not distract from your main subject. In some cases, it can be helpful to a composition to have some elements still be recognizable but slightly out of focus. Take the example of the birch branches above. The slightly out of focus branches create echoes of the in-focus subject.

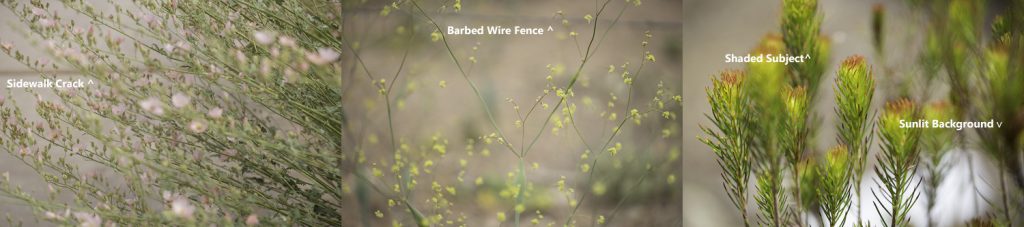

Finding subjects with attractive backgrounds is a major challenge of working in nature, as it is difficult to control the scene. Despite these issues, I always work to find a solution based on what is present and never default to using an artificial background of any kind. Often, a single glance through your viewfinder will let you know if it will be worthwhile to spend more time working this kind of scene, given the background options. Below, you can see some examples of where I should have been more careful about my background, with a crack in a sidewalk, a barbed wire fence, and a bright sunlight background interfering with my subjects. In each of the three examples above, I could have moved my position and eliminated these visual distractions pretty easily.

In addition to the subjects in your background, it is important to be aware of the lighting situation for the whole scene you are photographing – not just your primary subject. If your subject is evenly lit but the background is in bright sunlight, you will often get bright, distracting highlights in your background. While this effect can sometimes work, it often pays off to change your position or make your own shade to help create more even lighting. I carry around a portable diffuser to help with these situations, although a coat or backpack can work in a pinch. When using shallow depth of field, I often prefer heavily out of focus background elements with few details under soft even light, as this helps the main subject stand out and is often more visually pleasing.

While most of the photos in this post were taken under even lighting, other types of light can create interesting opportunities for photographing very small scenes. Photographing with the sun behind your subject, for example, can make translucent leaves or fuzzy edges of a plant seem to glow. Sidelighting can create strong shadows, offering another element to integrate into a composition. I took the photo above on a day with bright sun (I brightened the shadows in processing to soften the look). These different kinds of lighting can create additional contrast and stronger lines, both of which can help create more dynamic and striking compositions. Working with these alternative lighting scenarios takes a lot of experimentation, persistence, and perfecting your technique before things come together so be prepared to try again if your first attempt does not work out as you might have hoped.

Composition is the arrangement and flow of elements within a frame. In addition to light and subject selection, composition helps tell a story through a photograph. As the photographer, you are in control of what to include or exclude within your frame. For this kind of photography, your subjects will be small and thus, small details (and imperfections) carry a lot of visual weight and impact the success of your final result (for example, specs of dirt, a blemish on a leaf, or messy spiderweb can reduce the impact of a photo). Taking the time to carefully craft and then refine your composition in the field can help minimize negative surprises after you get home and look at your tiny subjects on a full-size monitor.

In nature photography, composition is often discussed in terms of a set of rules (like the rule of thirds). I personally stay away from such rigid guidelines and instead think of composition concepts as tools in a toolbox that can be applied in many different ways. In some cases, it makes sense to place a major element of a scene a third of the way into your frame (the in-focus birch leaves above). In other cases, it makes more sense to center your subject (the radiating yucca below). Thus, I encourage you to instead approach composition as a process of making deliberate choices about how to use your set of composition tools based on the needs of your scene and the story you hope to tell about your subject.

Composition concepts, like those discussed below, serve as building blocks to help you pull together elements of nature into a photograph once you start working with your camera. Another benefit of learning these concepts is that they also help improve your ability to identify opportunities in the field by honing your ability to see subjects in different ways. The ideas discussed below will help you distill what you see, start to identify subjects, come up with some initial composition concepts, and then refine the final result. Here are a few composition ideas to keep in mind when photographing plants:

Finally, I always consider visual weight when I am composing a subject and working with shallow depth of field. I think of visual weight as the amount of attention an element attracts compared to the other elements within a frame. Visual weight does not necessarily correspond to the physical space taken up by a subject, although larger subjects often to have significant visual weight. In some cases, a tiny object can catch a viewer’s eye and thus command a lot of visual weight relative to its size. Take the example of the photo above. The dark purple spot in the upper right corner is darker than the subjects in the rest of the frame. It catches my eye a bit so I lightened it during processing to reduce its visual weight and ability to distract from the rest of the photo.

Thinking about the visual weight of the objects in your frame can help you create a unified and cohesive composition. Because this approach to photography deals with such small scenes, tiny elements – like a bare patch of ground or a bright spot in the background – can carry significant visual weight and distract from the overall success of your photograph. Therefore, it is important to step back as you are creating a composition and think through how much visual weight the different elements in your scene hold and how they together affect things like your intended focal point(s), balance, flow, and continuity. If you find that something in your frame is carrying too much or too little visual weight relative to your goals for the scene, you can use this information to make adjustments to improve your composition (or know that you have something to address in processing).

The degree to which a photographer should process their photos is one of the great debates in the nature photography community, so I offer my practices here as a reflection of what I do, not what is the “right” or “best” approach. For my photographs of small scenes, I generally want my photos to stay grounded in the reality of what I saw through my camera when I took the photo. This means that I do not engage in significant cloning or clean-up but will address imperfections if they make up a small portion of the frame or do not significantly alter the subject. On the other hand, this kind of photography offers a departure from the reality of what we see with our eyes, so I feel some freedom to creatively process such photographs.

I see photo processing as a way to optimize my composition and subject after I get home. In the example above, the composition depends on the centered cactus, the radiating thorns, and symmetry. Because nature is never perfect, the left side of the frame ended up quite a bit darker than the right side. So, my processing focused on brightening up the left side of the frame and eliminating some of the distracting colors in the background – a common challenge when photographing plants in nature using shallow depth of field. To address these issues, I frequently use a technique called color painting, which adds a very soft overlay of color to an area of a photograph (in Photoshop, this starts with adding a new layer, selecting the ‘Color’ blending mode for that layer, using the eyedropper to select the color you want to paint from within the photo, reducing a soft brush’s opacity to 3-5%, and then gently painting over the distraction or problem area to ever so slightly soften a color or make it more consistent with the rest of the frame).

Cloning out minor distractions, contrast adjustments (both increases and decreases), color adjustments, and softening out-of-focus elements round out my typical processing choices for the photos you see in this post. Since I generally want my photos of plants to have a soft, elegant feel, I keep my processing mild in terms of contrast and color adjustments so that the grace, elegance, and softness of the subjects can shine through.

Next time you are out photographing, spend some time applying each of these concepts to help expand your photography toolbox. Start by slowing down and going through a visual inventory of what you see in front of you. Strive to notice the small details that make up the slice of the world you are viewing. After you notice the literal subjects that make up the scene, start looking for abstractions and think about ways you could use those abstractions to craft a composition. Once you have a scene in mind, pay attention to the details and be deliberate in your decisions about what to include and what to exclude. Spend some time moving slowly with your tripod and being more free-form by handholding your camera, working with different apertures to learn from your results. Experiment by trying new techniques to help stretch your creativity.

If you use shallow depth of field in your photography and have lessons that could benefit other NPN members, please share your ideas in the comments below.

Visit Topic or reply to this email to respond.

To unsubscribe from these emails, click here.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Gary Randall

Contributor

July 26 |

Originally published at: https://naturephotographers.network/articles/working-through-creative-slumps/

In a creative slump? Perhaps you’re experiencing some discouragement because it seems like everyone else is creating brilliance, but your own worst critic, yourself, is telling you that your work is junk. Maybe you feel that you’re just not progressing as fast in your skill as you think you should. I’m here to tell you that it’s natural. We all get into a slump now and then. We have our good days and bad days. Sometimes we feel inspired and encouraged while on other days we feel uninspired and ready to take up another hobby like cultivating moss.

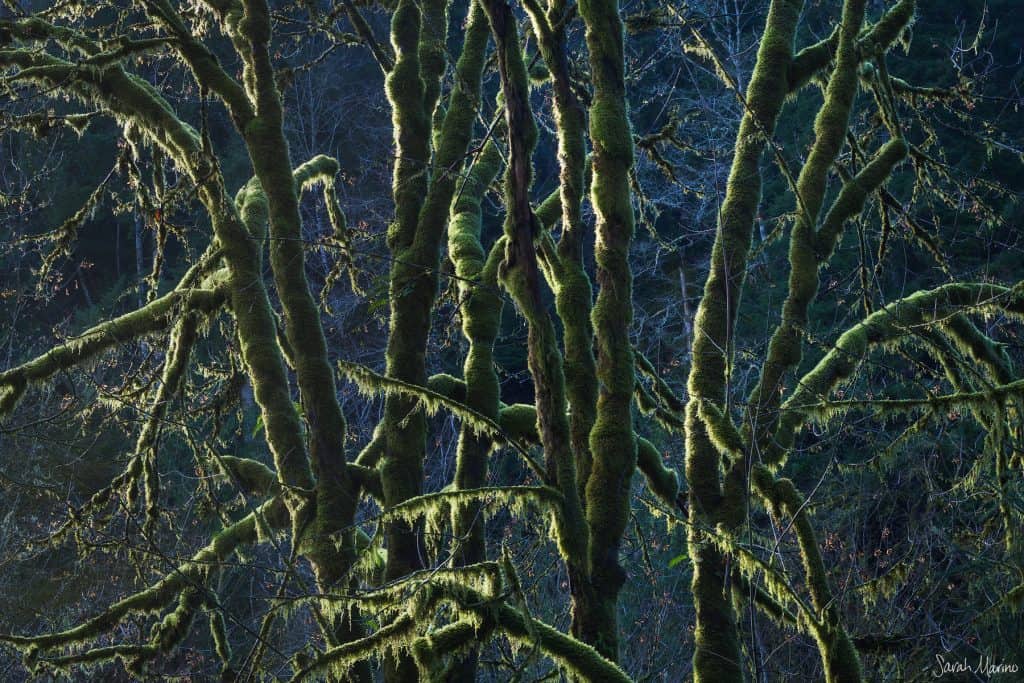

Mossy Vine Maple in the Mount Hood National Forest.

Mossy Vine Maple in the Mount Hood National Forest.

I’m certainly no psychology expert, but I’ve had my share of ups and downs. I’ve dealt with a few dips in the road, and a few tall hills as well. No matter how you cope with a slump, you must realize that, if your goal is to be the best photographer that you can be, you can’t let it discourage you to a point where you quit. Quitting is never an option for those who are determined. I understand that there could be solid, logical, and practical reasons for someone to quit photography, but for those who are determined, we learn to overcome these downtimes.

I’ve been asked how I get past these downtimes so I thought that I would list a few things that I do to get through a slump.

Relax and take more photos. This may sound like a simplification of a solution or even a bit of a cop-out, but it works. It’s like pushing through the pain. Don’t burn yourself out, but be a bit more casual about how hard you push yourself. There’s a good chance that this is why you’re in a slump. You’ve put a lot of pressure on yourself to perform. Relax a bit, but don’t stop. Go out and take more photos, but relax. It’s not a race. It’s a journey.

Compare your work with your work. I have struggled with this in the past, I will admit, but I feel that this is an essential thing to remember as you draw inspiration from others whose work you admire and want to emulate. It’s a strange brew that’s created with the ingredients admiration, inspiration, frustration with a dash of jealousy. Your photo idols can create this aura of unachievable mystical brilliance, but it’s usually something that we create in our minds. Many times it’s an illusion. Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain. The result, in many cases, is our creation of a set of unachievable and unrealistic expectations for ourselves. It’s fine to gain inspiration from others, but compare your work today with what you were doing a year ago or more. This is the way that you will see your progression and find encouragement to keep moving ahead.

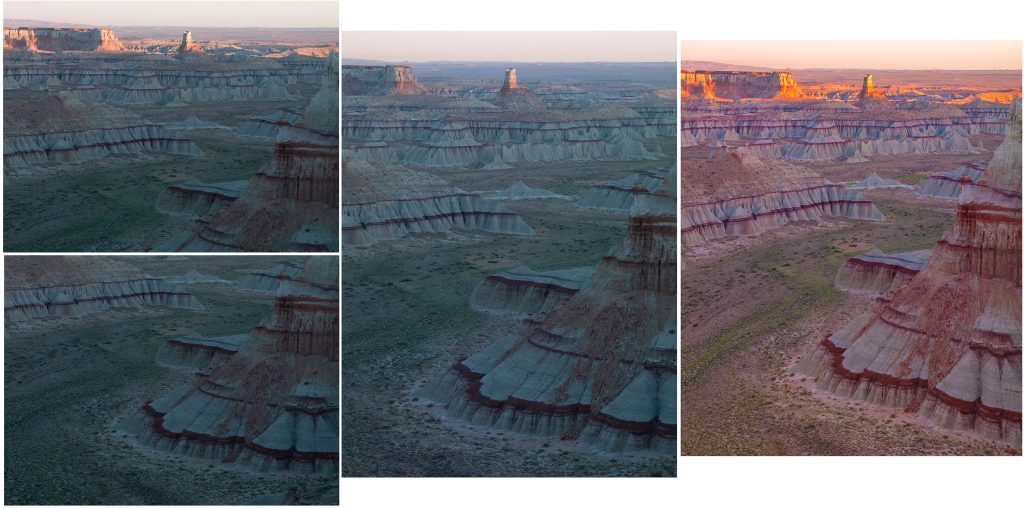

Same location – 2009 on the left – 2018 on the right.

Same location – 2009 on the left – 2018 on the right.

Get back to basics. Remember when you were curious about how to create with your camera? All of those little dials, levers, and mystical buttons were all things to learn. It made us feel as if we still had something new to learn, but it’s been my experience that most photographers find their own little shortcuts that allow them to create an acceptable photo. We all can get into a routine that works and feel uncomfortable if we have to hop out of that routine. Many times we allow the camera to make many of the creative decisions for us. Take your camera out and experiment with the three basic camera adjustments: shutter speed, aperture, and ISO. Be creative with them and experiment with them. It’s especially easy when using a digital camera because the film roll is very, very long with a 64GB memory card. Take a lot of pictures. You can’t screw anything up. Make a lot of mistakes. For every mistake made, there’s a lesson learned. Many times new-found skills, minus the shortcuts and special effects that were used prior, will move your work in a new and more inspiring direction. Another consequence is that you move further toward creating your style.

A photo taken with a wooden Zero Image 2000 pinhole camera using 120 color film.

A photo taken with a wooden Zero Image 2000 pinhole camera using 120 color film.Photograph something new. Routines can create slumps. Perhaps we’ve been spending all of our time trying to become the best landscape photographer that we can be and then, bam. We get to a point where we wonder what to do next. Photography is a very diverse art and skill in its application to everything from art, documentation, commercial, events, and portraiture. And each genre has its sub-genres. Don’t limit yourself to just one type of photography. Push yourself to take more portraits if you’re a landscape photographer, for instance. Maybe learn how to take some macro photos. Each type of photography has its methods that are exclusive to that style, yet teach us lessons can be applied in all styles of photography that we do.

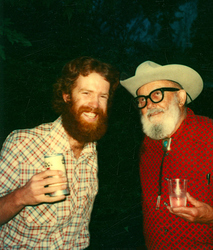

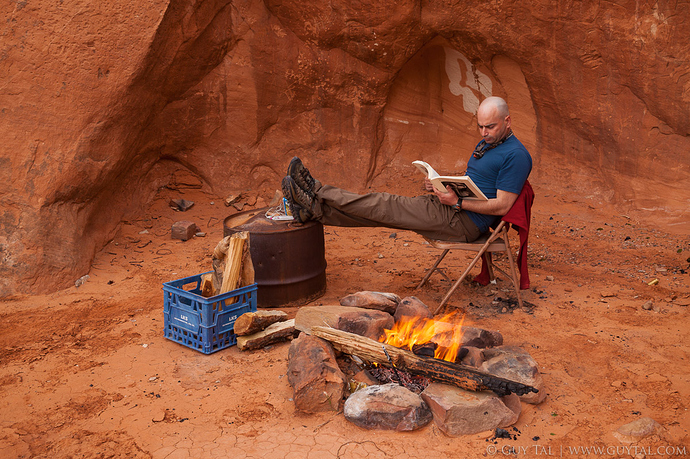

Mixing portraiture with landscape photography.

Mixing portraiture with landscape photography.Photograph something familiar. I know what you’re thinking. You’re tired of photographing the same lake that is near to where you live. Perhaps you’re tired of photographing your children over and over. Even my own Mount Hood can get a little routine when you live next door to it. I understand that. What I do is to try to reimagine different ways to photograph a familiar scene. I live very near the Sandy River and have photographed that stretch of river behind my home many times, but if I were to show a stranger who has never been there a dozen photos taken from within a 100-yard circle, they would think that each one was taken at a different place. Different points of view. Different focal lengths. Different depths of field. Different conditions and tones of light all create different effects to allow you to push your compositional skills, especially.

A photo taken a short walk away from my home on the upper Sandy River, Oregon.

A photo taken a short walk away from my home on the upper Sandy River, Oregon.But after all of that, the answer is as simple as this. Keep taking photos. Try new things and have fun, if you find that you’re not enjoying photography have a good honest talk with yourself about why. Many times the reason has little to do with photography and has more to do with our motivation for doing photography. Why are you doing it? What’s the purpose that it serves you in your life. Many people do it for reasons that are unfulfilling. A lot of people see it as a competition. Too many people photography is an art. It’s not a competition. There’s no room for competition in art. So relax and take your time. Work within your world and not others and keep taking pictures.

Visit Topic or reply to this email to respond.

To unsubscribe from these emails, click here.

|

|

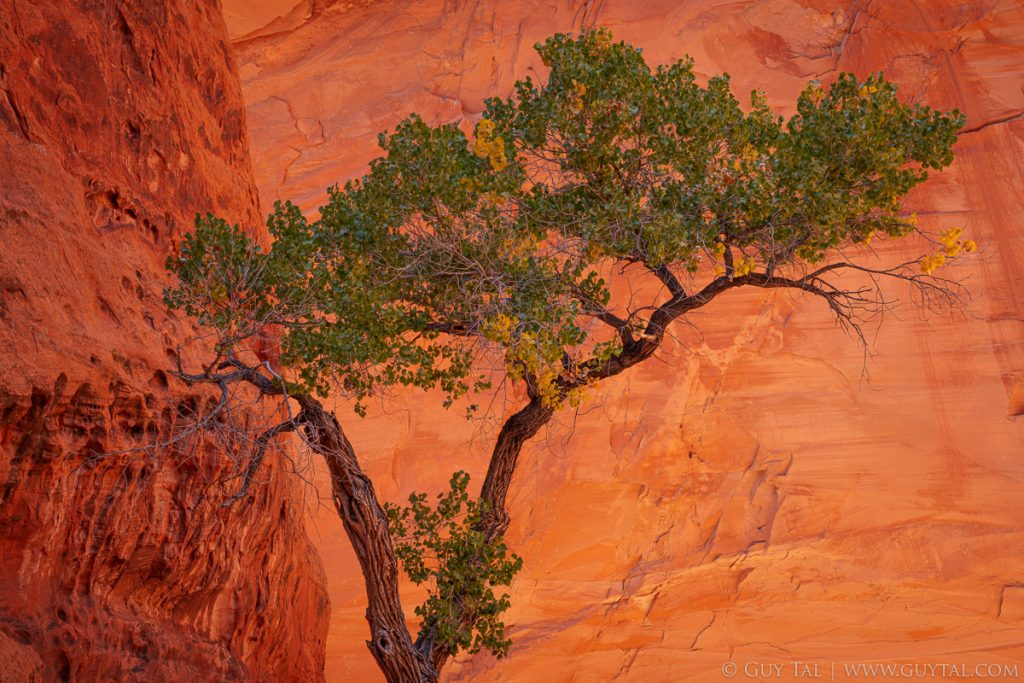

Guy Tal

Contributor

July 1 |

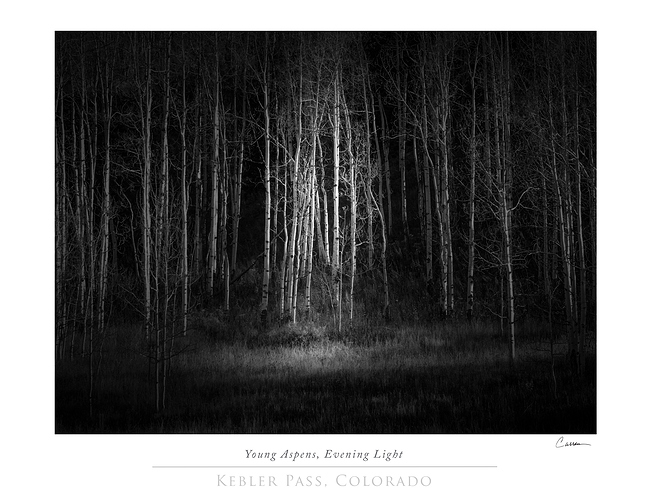

Originally published at: https://naturephotographers.network/articles/take-your-bearings/

“To chart a course, one must have a direction. In reality, the eye is no better than the philosophy behind it.”

~Berenice Abbott

As a child, I loved everything wild and natural. Animals, landscapes, trees, flowers, seashores, deserts, mountains—the more removed from the artificial world of humanity, the better. I spent much of my time in the fields around my home, observing lizards and insects, learning to identify flowers and birds and the cycles of nature. I read anything I could get my hands on, about natural places and things and adventures, and watched with absolute fascination the rare documentary film offered on occasion on the single channel of public TV available at the time. With the naïve imagination of a child, I dreamed of growing up to live alone in some remote jungle, picking exotic fruit from abundant trees, making friends with birds and beasts, and even learning their language. My childhood dream world was as rich and vivid and beautiful as anything you can imagine, and I was the only human being in it.

During my lifetime, human population had doubled, and wildlife population was cut in half. The correlation is not a coincidence. The trend continues and even accelerates. Numbers—empirical observations and statistical inference—tell us what so many public figures refuse to: there is no “fixing” such things as climate change, mass extinction, and so many other related threats.

I now look back across the decades at my childhood dreams with a mix of agonizing sadness and profound gratitude—sadness for all the loss and suffering, and for all the beauty never to be seen again; gratitude for what I got to see and experience, and for the life I have made for myself. The road was at times arduous and unpredictable, at times beautiful and gratifying, often uncertain, rarely easy, and yet profoundly satisfying. This is because, among so many mixed feelings I have today about the state of the world and the course of my life, one feeling is conspicuously absent: regret.

Unlike so many false prophets, I am not here to offer a message of blissful hope against the odds. I have no tips or tricks to help you find some fabled, easily-accomplished, “next level.” I am not rallying for any cause, and I have no assurances that everything will be OK. Hope is a powerful thing, but like all powerful things, it must be practiced with caution. This is because hope comes in many flavors, some beautiful and elevating, and others seductive but harmful. Of those kinds of hope to be wary of, one found in great abundance is false hope—hope for the untenable, hope that cannot be sustained without ignoring one or more inconvenient truths, hope that is not hope at all, but self-deception in disguise.

To my point here, another kind of hope to be leery of, is hope as substitute for action—hope regarding things that, even if difficult and risky at times, are within reach, but only if pursued actively rather than just hoped-for; hope that dismisses what is within reach for such rationalizations as, “someday, maybe, if.” The reason to be cautious of this kind of hope is that, if sustained for too long, waiting for some circumstances that likely (or surely) will never come, it ultimately becomes regret.

But some hope is good hope—elevating and motivating hope. In particular, there is a kind of hope that is very likely within your power to fulfill: hope for a day, after some years and decades of living, when you will look back knowing you’ve made the most of whatever gifts and opportunities came your way, whether successful or not. Where idle hope may lead to disappointment and regret, this kind of hope, which I call, “future hindsight,” often leads to pride and dignity, having proved to yourself that you are the kind of person possessing the courage and grit to remain true to who you are and to what is important and noble to you, to go about the world as you are, to persist through adversities, to embrace beauty where you find it, without cynicism and jadedness; to not shield yourself from, or numb yourself to, life’s most rewarding and rapturous offerings.

If, like me, you find meaning and purpose in things wild and natural, and are consciously resistant to such things as cognitive dissonance and motivated reasoning, the conclusion is difficult to avoid: your opportunities for wild experiences are diminishing rapidly. My goal is not to discourage you, but in fact to do the opposite: to encourage you to consider that in matters having to do with wildness and natural beauty, and certainly in matters having to do with making the most of your living moments, don’t let false hope blind you to real urgency.

Should you come to this conclusion, you will find yourself at a point of decision: you may become discouraged and unmotivated; you may spend your days in jaded frustration, bemoaning your misfortunes; you may find meaning in fighting for some cause; or you may come to realize that, regardless of what the far future may hold, you still have much opportunity for beautiful, meaningful living, still available to you. There is no purpose in decrying things being lost, while failing to appreciate them while they still exist. Dare to hope for something that is neither about “winning” or “losing,” nor about platitudes and seductive impossibilities—dare to hope for something that is as noble as any cause or struggle, and that is almost certainly possible if you commit yourself to it: hope to someday take pride in having lived a fulfilling life; hope to spend as few of your conscious, living, moments as you can, feeling bored and uninspired.

I never believed in long-term plans, and have often felt grateful to my younger self for not making them—for not locking me into some preconceived course, no matter how “right” or tempting it may have seemed at the time—knowing that the person I will become in time will be wiser, more knowledgeable, and more experienced; and would appreciate as much freedom as I could leave for him to make his own choices.

Photography is among those choices that likely are as safe as any, and that have the capacity to enrich your life, but don’t take for granted that photography of natural things will, by necessity, be your creative outlet, your contribution to conservation, your vocation, something to “get you out of the house,” or any other thing. Certainly, photography can be all those things, and more, but in itself it is none of them. If such things are important to you beyond just being rationalizations for spending money on camera gear, you have to choose them, to assimilate them into your attitude toward life and photography, and to work to accomplish them.

In proclaiming such things, often people ask what’s wrong with just taking pictures? What’s wrong with photography being just a pleasant pastime? An entertaining distraction? Something to do on vacation? A means of sharing experiences with others? What’s wrong with doing the easy and obvious? These are unproductive and unnecessarily-indignant questions. It’s not about whether such things are right or wrong in the abstract, it’s about being honest with yourself about whether they are right or wrong, for you. It’s not only about the value you get from practicing photography in some ways, but also about what you may be giving up, perhaps without even knowing it, by not practicing photography in other ways.

Should you realize that just taking pictures fails to satisfy, and should you decide to find out what value there may be in pursuing photography in other, perhaps more difficult and more consequential ways, you likely will find yourself at a loss for how to get there, if only because you cannot define what “there” is. Realize that your “there” may not be like anyone else’s “there,” and that you may not know what your “there” is until you get to it. The only way forward requires not so much taking a leap of faith, but recognizing that certainty is an illusion, and that anything you do is a leap of faith. Even taking a seemingly-safe route, you still risk losing much by denying yourself opportunities.

If you wish to become a commercial photographer, a photojournalist, a conservation photographer, a social media star, or anything else—pick a direction and make a step in this direction, not with the naïve hope that you will get what you want by following your bliss, but with courage and intent, and acknowledging there may be worthier things still ahead that you did not even know to hope for. You will know you are truly following your bliss, not when you get where you thought you wanted to go, but when the following becomes the bliss; when you find satisfaction, not when some work is done, but in doing the work.

Of the many directions possible in photography, I chose photography as art. I’ll give you the sales pitch, not because I believe that art is necessarily the best or only worthy direction in photography (an admission you will rarely hear from disciples of more militant photographic factions), but because it happens to be a direction I know something about, and because it has transformed my life in ways more spectacular than I even knew to hope for. That said, I acknowledge also that living as an artist is not for everyone.

Of all the purposes that photography can serve, art is a peculiar one, and different from the others in some important ways. One distinction of photographic artists is that we are perhaps the only group not in the habit of telling those who pursue other genres, that what they do is not “real” photography. Joking aside, it is my estimate that those committed to photography as a medium for artistic expression, generally spend considerably more time and effort practicing our work and honing our knowledge and skills, than bickering about it. This is because we don’t photograph for the glory of the photographic medium, to justify our membership or ranking within some photographic tribe, or to “win” any arguments; we photograph primarily for the rewards of engaging in creative work, which amplify in direct correlation with the time, effort, and dedication we put into it.

In my way of working, making art is not the purpose of living as an artist. Rather, making art is a means of sustaining the life of an artist and reaping its great personal rewards, some of which have little-or-nothing to do with art or photography. Certainly, such rewards are not often financially-lucrative, but are nonetheless valuable. One such valuable reward is freedom. Not beholden to any “rules” of any “game,” we have the great privilege of being free to practice our work with as much seriousness and dignity we feel it deserves, and needing no other reason or justification to care deeply about what we do and why we do it.

To some, an artist is simply one who makes art. Such a definition is perfectly suitable for those satisfied with short-lived reprieves from otherwise-less-satisfying pursuits. I tried it. It bored me. To persist in photography, I needed a better reason than photography just being more enjoyable than the tolls of a high-stress job or the frustrations of rush-hour traffic. I didn’t want art as a distraction from life, I wanted a life in which such distractions are unnecessary—a life expressed in, and elevated by, art; not a life escaped from in art. As such, photography to me is a medium for creative expression—a means to an end, and not, as it is to some, a practice to engage in only within the bounds of strict commandments and under quasi-religious tenets of contrived purity. For what I’m after, photography is no more sacred a medium than poetry, dance, or sculptures carved in butter: it’s an incidental “how” that happens to be suitable to my much more important “why.”

The kind of artist I aspire to be is not just one who makes beautiful art, but one for whom beautiful art is the byproduct of a beautiful life: one who feels powerful emotions and surrenders to them without inhibition; one who cares deeply and unapologetically about things, without need to tame passion or to be concerned with the judgment of others; one moved to seek and discover novel ways of assimilating and engaging with the world; one who revels in becoming educated, knowledgeable, and skilled, not in order to compete with others but because it makes me a better artist, and the better I get at my work, the more rewarding it is to me.

My catalog of photographs is not a collection of neatly-categorized records of places, things, and events; it is my life story, in all its dimensions and nuances, encoded and expressed in visual compositions. When I survey my past work, I don’t see pictures of this or that; I relive experiences. I’m reminded of times of metaphorical, and not just literal, light and darkness; I recall sensations and thoughts and emotions; I project myself back into moments of awe; I revisit hard-won lessons and random epiphanies; I sometimes re-examine my priorities, in life and in art. Often, I don’t remember without looking, what camera I used.

My life as an artist may not be easy, but it is beautiful to me. And I get to say that with a straight face, not as a platitude but as a statement of fact. I can’t say the same about any other life I’ve had.

In a letter to his son, Sherwood Anderson wrote, “The object of art is not to make salable pictures. It is to save yourself.” If you believe the life of an artist is for you, and if your art is founded in things wild and natural, and if you are prepared for the challenges, make a step in this direction—if only in your attitude and seriousness toward your work. You may well realize some years from now that, even though you couldn’t save the world, you may have saved yourself from the abyss of drudgery, boredom, and regret.

What do you wish to do next? Whatever it is, don’t wait. Take your bearings, pick a direction, and take a step. Whatever step you take, it will put you in a better position to decide the next one. Unlike so many grandiose plans, taking just one step in the direction of your hopes, even if rife with fear and uncertainty, even at the risk of breaking with tribal allegiance, is within your power.

Visit Topic or reply to this email to respond.

To unsubscribe from these emails, click here.

|

|

Alain Briot

May 31 |

Originally published at: https://naturephotographers.network/articles/esquisses-and-raw-files/

Ansel Adams said that the negative is the score and the print the performance. Adams used film, but if we make a parallel with digital photography, the raw file would be the score, and the converted and optimized image the performance.

The problem with comparing a raw file to a musical score is that by nature, a musical score should be inspiring and invite interpretation. I find raw files quite uninspiring and hard to interpret. On top of that, some of my photographs are warped to remove curvature created by fisheye lenses while others are collages of multiple captures used to create a wider view than a single capture can create. In this context, what is the score? What is the original image? Is it the original capture, is it the warped image with the distortions removed, is it the collage? Hard to say. One thing is sure; there is no original score, nothing set in stone or written down. There is nothing to interpret. Instead, there is everything to create. This is raw material, not score material.

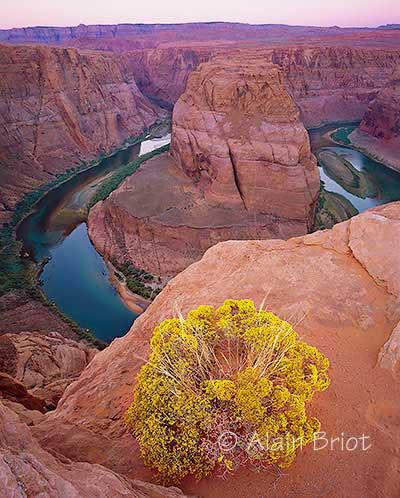

Raw file and the final image

Raw file and the final imageFor these reasons, I prefer to refer to a raw file as an esquisse rather than a score. An esquisse is a quick sketch or a rough drawing of the general composition of a picture or a painting. It is a term used in painting and drawing, a term I learned and used at the Beaux Arts where I studied painting and drawing. The goal of an esquisse is to nail down the main elements: their shapes, their proportions, and their location in the composition. An esquisse is indicative of the final painting in a very loose manner. It is understood that it is meant to be seen by the artist only and used as a guideline. It is intended to be the first step of a long process. It is understood that the final painting will cover the esquisse completely, that eventually, the esquisse will be invisible and that it will be changed over time as the artist progresses towards completing the finished painting.

Sunrise in Western Navajoland

Sunrise in Western NavajolandIf we make a second parallel, this time between film photography and painting, the negative would be the esquisse and the print the finished painting. However, as we have seen, unlike a musical score, an esquisse is not meant as a source of inspiration. Instead, it is intended as the beginning of the work, as a first ‘jest’ so to speak, a first idea, a guideline. The inspiration, when referring to the process of painting, is not the esquisse. The inspiration is the subject itself, be it a human figure, a model, a still life, a landscape, a building, an animal, or any other subject.

In that sense, painting differs from music in that the painter finds his inspiration in the subject itself while the musician finds his inspiration in a subject from which he writes a score, which he later interprets. The painter, therefore, experiences a more direct connection to the subject, the inspiration being the subject itself and the esquisse being only a temporary step between subject and painting, a step intended only as a guideline and not meant to be kept, preserved or shared in any way. An esquisse never goes beyond the stage of being rough, and is usually only understandable to the artist who created it. This is the opposite of a score which, being intended for public sharing, is inevitably polished and made understandable to all through the careful and deliberate use of musical notation.

Because the esquisse is meant only as a temporary step in the creation of a process, only on rare occasions is it seen by anyone else besides the artist. It remains a private representation, not meant for public display. As such, the same esquisse cannot be used more than once, and neither can it be used by other artists. This is fundamentally different from a score which, once written, is meant to be used each time a musical piece is played and is meant to be used by whatever musician wishes to perform the specific musical composition described by the score.

As such a score is intended for interpretation, and as such, it is open to each musician’s idea of how it should be played. The esquisse, on the other hand, is not meant for interpretation and is only intended only for a specific artist’s eyes.

An afternoon at the Confluence

An afternoon at the ConfluenceLet’s return to photography. My point is that I see more parallels between a raw file and an esquisse than between a raw file and a musical score. The comparison between a black and white negative and a musical score made sense because the photographer had altered the negative in the darkroom by developing it with a specific goal in mind. Using the zone system together with a variety of development processes, the photographer could develop the negative to reduce or increase the contrast as well as set this contrast to precise density values. This controlled processing cannot be done with a raw file. All we can do is control the exposure and set the color balance, and color space, and that is about it. Furthermore, all these parameters will be reset during optimization because most raw files are overexposed to maximize digital data recording and because color space and color balance are ‘soft’ settings that can be changed at will during optimization.

All this makes letting someone else than the photographer interpret the raw file challenging. It has little in common with the way a musician interprets a score. Certainly letting another photographer process the raw file would result in a different version of the image. However, I doubt this version would have much in common with the original photographer’s intent. There is just too much left to choice, too many variables to adjust, too many important decisions to be made. In the end, rather than seeing an interpretation of the original image capture, we would witness the creation of a new image, one most likely, unlike the one the original photographer created.

Sun Star in Blue Canyon

Sun Star in Blue CanyonI construct images; this is what I do. I don’t just capture raw photographs, process them, and convert them. I alter them, warp them, and reformat them. I change their color palette, I dramatically modify their contrast, and I use every digital means available to me to make them look the way I want them to look. I like to joke that I do unspeakable things to them; except I am not joking. For me, these things are not unspeakable. They are enjoyable, liberating even. But for those who continue to follow a strict film paradigm, a rigid way of processing images that is limited to adjusting color and contrast, the things I do -are- unspeakable. However for me, for someone who was never happy with the limitations that film imposed on my creativity, for someone who was trained as a painter and did not understand why shapes and colors couldn’t be molded to my desire instead of being fixed by the film they were recorded on, these things are a dream come true. A godsend. A response to my prayers. A medium that opens the doors to a full set of creative tools. I make no secret that if it were not for digital capture and processing, I would have quit photography long ago. I may have gone back to painting, since this is the medium I was first trained in, or I may have done something completely different, but I would not have pursued using a medium that had so many limiting and frustrating aspects.

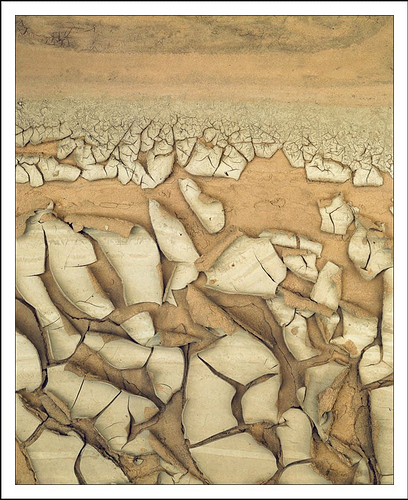

Sunrise in the Clay Hills

Sunrise in the Clay HillsThis essay focuses on explaining the thinking process I go through when I create digital images. This thinking is non-verbal. It takes place in my mind, and I am not necessarily aware of it when I work. Neither do I need to be. Only the result counts. If the image turns out to be what I want it to be, I am pleased. However, to write an essay like the one you are reading, I have to make this process conscious. So I started taking notes when I work on my images, and I began saving photographs of the process I follow as it goes through its different stages. It is these notes that are behind this essay, and it is these photographs, both the original and the final versions, that illustrate it.

As you can see, the changes are radical, and the differences between the original raw capture and the final image are dramatic. If presented alone, the final image gives no indication about the look of the original raw file. This is why I featured both the before and the after versions next to each other in this essay.

Visit Topic or reply to this email to respond.

To unsubscribe from these emails, click here.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

James Lorentson

Contributor

August 6 |

Originally published at: https://naturephotographers.network/articles/are-your-landscape-compositions-lacking/

“Another article on composition?” Yes, but I promise not to babble about the merits or drawbacks of the rule of thirds. I bet you already know plenty about compositional tools. Understanding what tools to use is crucial and grants you tremendous artistic power. But it’s not enough. You need to know how.

It’s not your fault. Too often, the books, articles, and videos on composition start and stop with the tools. But you must use the tools like a chef uses ingredients—you don’t want to throw everything into the pot and hope it tastes nice. You must deliberately choose and balance the different ingredients in a way that achieves a cohesive taste. Or in our case…a cohesive story.

With photography, that can sometimes mean, for instance, that a natural frame should be discarded for the sake of simplicity. Or maybe a more intimate scene captures the mood better than a grand vista. Your vision is your anchor. It’s the starting point from which all decisions should follow. In this article, I’ll share my process for creating cohesive and deliberate compositions that are rooted first and foremost in you as the photographer.

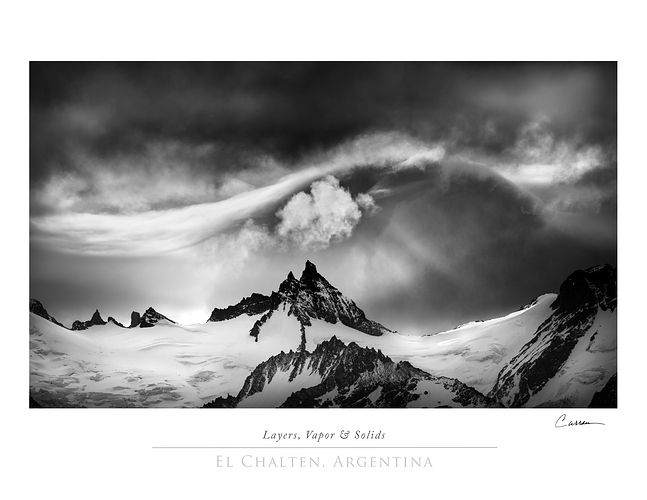

Imagine this… As you open your car door, the wind blows rain straight into your face. It’s pouring. It’s cold. It’s dark. A golden hour sunrise is off the menu. You consider turning back, but you’ve traveled hours to get here, you’ve brought the right gear, and you’re already awake. So you push on. As twilight lifts the veil on a new day, you spring into action. A short, steep hike up a rocky trail reveals a valley coated in fog. You’re now running! Tripod, remote release, filters, air blower for the raindrops—the race is on to find a composition. Soon, you’ve found a spot and begin racking off frames.

For the first ten minutes, that was me. I ran around like a crazy person looking for the “right” foreground tree. It wasn’t until I slowed down and questioned the focal point that I saw how the two gnarled trees complimented the two streams of the river.

In a situation like this, how would you have chosen what to include and exclude from the frame?

Before we get into solutions, let’s look at common reasons you may struggle with composition:

I’m guilty of all the above. A few years ago, I decided I needed to do something different. So I collected my thoughts and notes on composition and typed a set of prompts to use in the field. I printed it out to place behind my camera’s LCD and digitized it to my phone. If I look back, it wasn’t the ‘leading lines’ I needed help to remember, it was slowing down and tuning in. I now share a digitized copy with my workshop participants, and I’ve found it has made a big impact on how they approach a shot.

The compositional tools address #2 and #3 above. Chances are, you’ve got those covered. We’ll focus on #1–telling a deliberate, cohesive story.

There is nothing worse than a sharp image of a fuzzy concept.

–Ansel Adams

The creative path begins with you. It’s your job to write the story. The moment you see something you want to shoot, you owe it to yourself to tune in and find your voice. Listen, trust your intuition. Do so and you will have a deeper place from which to create your art.

Resist the urge to grab your camera. You must explore your subjects before you have meaningful things to say about them. Study the details and the relationships between the different elements in the scene. Train your eye to the full potential of your subject.

Power is mass multiplied by cohesion.

–Edward Luttwak

Decide what your photo will say and then choose how best to communicate that message. The focal point is not your composition. Your view on the focal point is the composition. It isn’t what the scene looks like, it’s what you say about it.

Each decision you make in the field should take into consideration your unique viewpoint.

Even when you’re in the most familiar situation, you can look for new opportunities.

–Corey Rich

Now, grab your camera (without the tripod) and work the scene. Use the compositional tools to help tell the story.

Simplicity is about subtracting the obvious and adding the meaningful.

–John Maeda

Each character in your composition should have a role that adds to the story. Our brains are good at looking past distractions that will show up in the photo. Move in closer, zoom in, or change positions; remove everything from the frame that doesn’t contribute to your story.

The first couple of times you answer these questions, it may seem weird, even pointless. But if you try it, you will tap into creative energy buried deep in the subconscious. If you’ve been at this for a while, you already consider some of the prompts above. Still, if you slow down and make every step deliberate, I promise you’ll improve your results.

Composition is the most crucial skill to develop in photography. And unlike weather and natural light, composition is under your control. If you sign up for my mailing list, you can download a PDF of the above prompts and a bunch more. Save it to your phone to use as a reference before your next shoot.

Like many creatives, you may view structure and process as inhibitory. While free-thinking and a non-linear approach benefit creativity, some structured prompts help you execute. Part of this amazing craft is learning to balance structure and technique with intuition and creativity.

If you take one thing from this… It isn’t what you know, but how you use that knowledge. You don’t need any more rules. You need a method to discover and extract the parts of the scene with which you resonate.

That’s all for this one. I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments. Until next time, wishing you grand adventure and good light!

Visit Topic or reply to this email to respond.

To unsubscribe from these emails, click here.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

NPN_Editor

Nature Photographers Network

August 25 |

NPN is excited to announce our first-ever Ask Me Anything (AMA), and our first guest is the highly respected landscape photographer Sean Bagshaw! This is your chance to ask Sean any burning questions you have about him, photography, or anything else on your mind.

This will be a live event that starts on Tuesday, August 27th at 2:00 pm EST and will only last for 24 hours. When the event starts you can find it at the link below and everyone is welcome to participate. You won’t find anything there until the event is live.

To add this event to your calendar look for the add to calendar button at the top of this topic, If you are viewing this message via email please click the ‘Visit Topic’ button at the bottom of the email to view this in a browser. You will also receive an email when the event goes live.

If you are not interested in AMA’s and don’t want to receive emails about them in the future please go to your Notification Preferences and remove ‘Ask Me Anything (AMA)’ from the ‘Watching First Post’ section.

Your local time for the event:2019-08-27T18:00:00Z UTC ? 2019-08-28T18:00:00Z UTC

Visit Topic or reply to this email to respond.

To unsubscribe from these emails, click here.

|

|

Sean Bagshaw

Contributor

August 27 |

Hi NPN!

I am Sean Bagshaw.

You can see more of my work here, if you are into that: https://www.outdoorexposurephoto.com

I’m a full-time photographer and photography educator and I’m also one of the members of the Photo Cascadia team. I’ve been on NPN since the early 2000s. The Photo Cascadia members all met through NPN. It’s also where I got to know Tony Kuyper a little before he published his very first luminosity mask tutorial here back in 2006. These days I split my time between my own photography work and teaching photography. I lead workshops with my Photo Cascadia mates, speak at photography conferences and also produce video tutorials on image developing and to teach Tony’s TK Panel.

As I often tell people, I spend as much time as I can out taking photos…sleeping in my truck, stumbling around in the dark, eating bad food and avoiding showers.

I’m excited to be answering your questions for 24 hours starting at 2:00 pm Eastern Time, August 27. I’m happy to answer any and all questions you might have…taking photos, developing, luminosity masks, gear, travel, adventure, photography biz, tall tales, how to avoid showers…just ask away below.

Posts not following these guidelines may be removed by moderators to keep the Q&A flowing smoothly. Thank you!

Visit Topic or reply to this email to respond.

To unsubscribe from these emails, click here.

|

|

NPN_Editor

Nature Photographers Network

August 28 |

It has been one year since we announced the relaunch of NPN! At that time the site was down to 250 devoted paying members, since then we have grown the site to 1684 members, 507 of which are paying members, along with 230 lifetime memberships that we honored from the old site.

We wanted to keep growth slow in the first year to have the flexibility to figure things out as we go and make changes as needed to make the site function in the best way possible. Not growing too fast allowed us to do things like adding the free membership tier, which has been a great success and will continue to help grow the site sustainably.

There have been many changes made in the past year based upon member feedback, which is precisely what we wanted, and we still have a few more tweaks to make. We’ve had hiccups along the way and learned a lot, and we appreciate all your patience through these times. We feel we are getting to a point where the site is highly polished, functional, and becoming less intimidating to new users, but we will continue its evolution.

We want to thank all of the moderators who are the backbone of NPN; without them, NPN wouldn’t be possible. They give their time selflessly every day because they believe in the vision and community of NPN. Thank you to all the paying members as well, you keep this dream of reviving NPN financially viable and ensure it continues for many years to come.

There is a lot to be excited about in the coming year; we have many big plans to improve the content on the site and to grow our membership even more.

In the coming weeks we will be sending out a survey to the members to get your feedback on the new site; what you like, what can be improved, etc. We will continue to work hard at making NPN the premiere site for nature photographers!

If you have any questions about the past year or our plans for the future feel free to ask, we try to be transparent as possible!

Visit Topic or reply to this email to respond.

To unsubscribe from these emails, click here.

|

|

Eric Bennett

Contributor

September 1 |

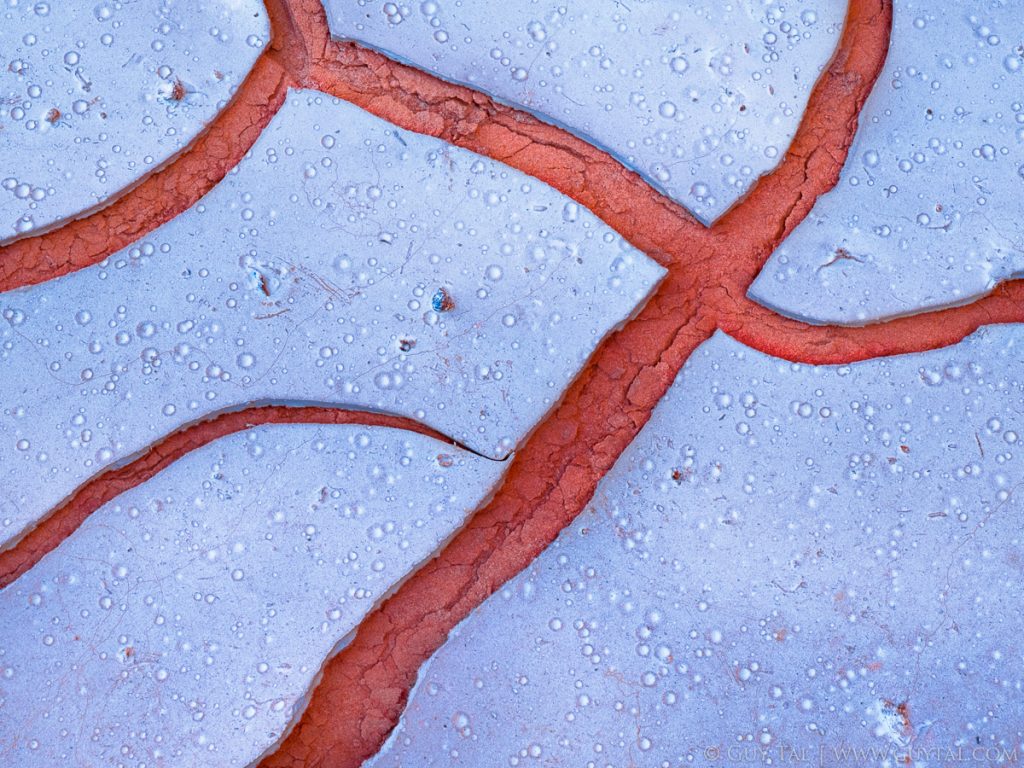

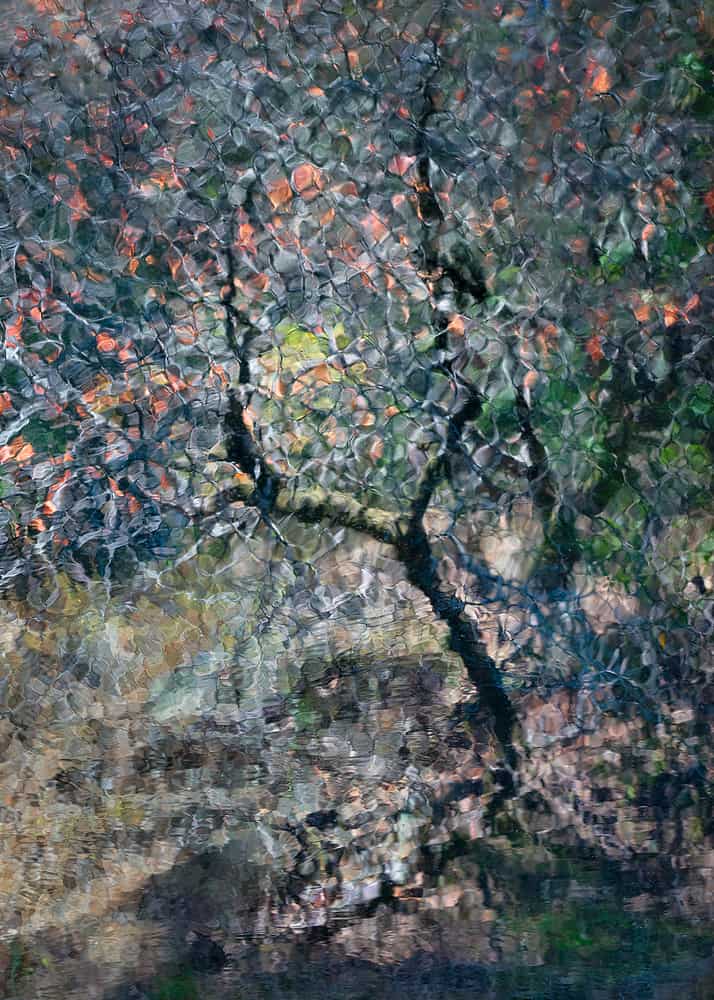

Originally published at: https://naturephotographers.network/articles/turning-down-the-volume/

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away, Heavy Metal was my favorite genre of music to listen to. Growing up as a teenager, my friends and I would push the poor stereo to its limits, blasting Slayer as loud as we could while driving around in my dad’s car, headbanging, yelling, and blowing out the speakers. Whether we were going skating, getting food, or just on our way home, it would get us pumped and make us feel alive. There were bands out there that understood us, what it felt like to be an outsider, to be angry at the world, and so we listened. Any metalhead knows there is only one acceptable volume for rocking out, and that’s cranked up all the way!

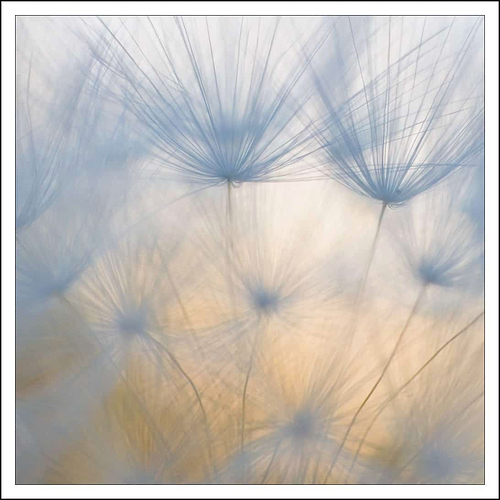

“Ripple Effect” Death Valley, CA

“Ripple Effect” Death Valley, CA

What separates Metal from other musical genres is that right off with the first chord, instead of slowly building, most songs start at 100% speed and volume (if you want to see what that sounds like listen to “A Corpse Without Soul” by Mercyful Fate). From there, the volume and fast tempo are maintained as loud as it goes all the way until the end of the song where it usually ends abruptly like running into a brick wall. Play as hard and loud as you can from the very start to the very end. Even bands like Metallica tried to record the ‘loudest’ albums ever, by using equipment that could record the instruments plugged into powerful amplifiers at their highest levels. For a long time, Metal followed this trend while in this sort of ‘noise war’ to see who could punch it up the loudest.

By now, you’re probably saying, “Wait? Wasn’t this supposed to be an article about photography? Where am I?” I know, I know, I’m three paragraphs in, and you’re scared this is going to have nothing to do with how you can take prettier pictures. Or maybe this is sounding all too familiar, and you are already making the connection on your own. Just stick with me here, I am about to make a face-melting point! While the photography medium doesn’t have a ‘volume’ slider, it has its own kind of noise, especially when thrown into the fast-paced world of social media, where thousands and thousands of visuals are trying to steal our attention every minute.

“Golden Rain” GSENM, UT

“Golden Rain” GSENM, UT

Because of this, I see a lot of photographers falling into the same kind of ‘noise war’ where they crank up the color, saturation, light, and subject matter, all in a desperate attempt to say “Wait, don’t look over there! Look at me!” Trying to demand someone’s attention by yelling at them can be effective, but is it the best way to keep them listening? Just like nowadays when I will occasionally break out the old records (really meaning just searching on Spotify) and rock out to some ol’ Heavy Metal classics, my ears can only last through a few songs, like most normal people, before they get fatigued. In the same way, I can only be on Instagram, 500px, and Facebook, for a few minutes before my eyes become tired from visual fatigue.

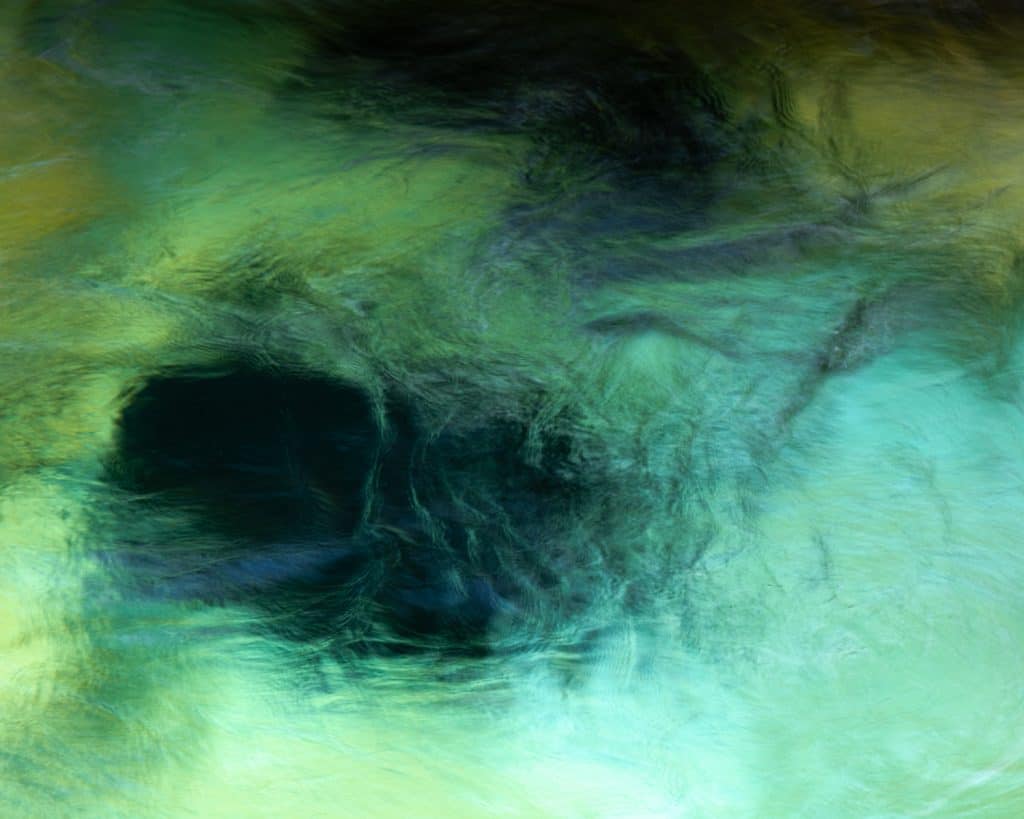

“Deep Purple” Ouray, CO

“Deep Purple” Ouray, COWhen you think of a quieter photo, what comes to mind? Probably a photo of simpler subject matter, maybe more abstract, without an obvious composition. It’s probably not as colorful or even black and white, doesn’t include as many objects, and requires more time and attention to understand and digest. Now, I’m not saying that you should not crank up the volume and shoot crazy light over big scenes that call for including more objects and being a bit more liberal with those photoshop adjustments. No, not by any means. I am trying to point out that if you continually play one note, at one volume, always portraying the world in the same way, eventually you are going to tire your audience, and most likely burn yourself out as well, rubbing the senses raw.

“Solace” Colorado Plateau, UT

“Solace” Colorado Plateau, UT

When I look through a photographer’s portfolio, the thing that makes me decide on following them or not, keeps me coming back for more, and impresses me the most, is that they have a wide variety of images in their gallery — ranging from very loud and powerful to very quiet and subtle. Looking through a gallery of images all cranked up to the same volume gets tiring, boring, and monotonous. After a while, it just feels like the same image, taken over and over again in a different place. This is why I feel that creating a tasteful portfolio takes some skill. For a body of work to be compelling, visually pleasing, and continually interesting from the first image to the last, there needs to be a lot of variety from each image to the next in scenes, lighting, processing, simplicity, mood, and color. This demands much more from the artist rather than letting them play the same note time and time again, merely repeating what they know best.

“Observers” NSW, Australia

“Observers” NSW, Australia

It’s true, the crazier, louder, and more ‘epic’ scenes will probably grab more attention on social media. But is that all there is to creating art? Is it just all about getting others’ attention by any means necessary? Well, have you ever thought about what you want to tell them once you have their attention? This is why today it is even more important than ever to know what your purpose is with sharing your images. If you are caught in the ‘noise race’ of trying to grab attention wherever you can, you will find yourself always looking for the same kind of crazy scenes and cranking the sliders to +100. You can only go so high, and so you will eventually plateau there, with nowhere else to go.

“Frozen Over” Uinta National Forest, UT

“Frozen Over” Uinta National Forest, UT

If you have found yourself stuck with your head at the ceiling, not seeing any more ways to outdo yourself, I have good news! You always have somewhere else to go! Back down. Take some time to explore areas you are less comfortable in, thinking about scenes you have never tried to shoot before, lighting that you usually write off as ‘bad,’ using lenses you have yet to experiment with, techniques you haven’t yet mastered. There is nothing more exciting, like trying something new! Don’t let yourself get caught in the ‘one-trick pony’ mindset, find your limits, and go past them. It’s the only way to expand your artistic abilities. It’s also the only way that doing the same thing for years and years can remain interesting. So many photographers fail to do this, which is why so many drop off after just a couple of years. They’re burned out from trying to keep up in the wrong way.

“Agave Dreams” Anza Borrego, CA

“Agave Dreams” Anza Borrego, CA

From my experience, the smaller, simpler scenes are what have caused me to grow the most as an artist, and better understand principles like composition, lighting, and color. Making something compelling within a smaller area or with fewer objects to combine is naturally more difficult, and you have fewer crutches to lean on. It is harder to hide imperfections when you are zoomed in on the details. Your mistakes become more noticeable both to yourself and your viewers. Because of this, you will probably fail more often than when shooting the big, more iconic scenes with epic sunset skies. The quieter scenes have nothing else to rely on besides your creativity and skills. But with each failure, we learn something new, and over time, with enough determination, you will begin to figure it out and see the world differently. Like anything, the increased difficulty also causes increased satisfaction when you do succeed.

“Art Bars” Colorado Plateau, UT

“Art Bars” Colorado Plateau, UT

Quiet photography, instead of yelling at people to look, sits, and waits. It patiently stays hidden until those who are truly seeking something different, something more profound, come and find it. This is where the artist’s personality can stand out and be felt by the viewer. Not by what you do like everyone else, but by what you do differently, (“Your art is not to be found in the things you do like other people, but in the things you do differently than other people.” – Guy Tal) and that will create a special connection with all those that understand your imagery. These kinds of deep connections with peers and fans are much more rewarding to me than the superficial, shallow imagery that tries to appeal to everyone.

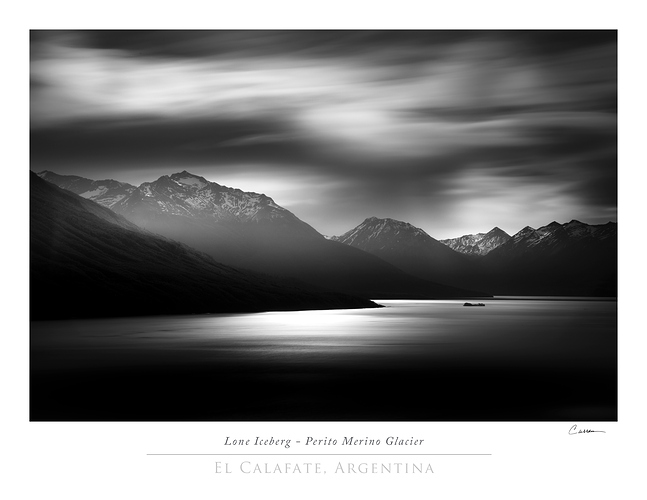

So how are you supposed to know when it is more appropriate to let the image be loud and intense or quiet and subtle? It all depends on the scene in front of you and how it speaks to you. An image that comes to mind from my portfolio is a photo from my first trip to Patagonia, Argentina, back in 2017. It was an extremely windy morning and waves, some a meter high, were continuously breaking near the shore on a big, glacial lagoon. The waves were causing pieces of ice that had calved off the glacier to rock around as they violently crashed against them. There was also intense light hitting the peak and surrounding clouds. Initially, I pulled out my telephoto and was trying to shoot more intimate scenes concentrating on the breaking waves and icebergs, but this wasn’t allowing for enough context. It could have been a picture of waves on the ocean, in somewhat ordinary lighting. What was making this moment extraordinary was the fact that there were big, powerful waves breaking, not in the ocean, but in a glacial lake, high up in the mountains, something we rarely see, even in Patagonia. The only way I could portray this to the viewer was by including the rest of the scene.

“Wake” Patagonia, Argentina

“Wake” Patagonia, Argentina

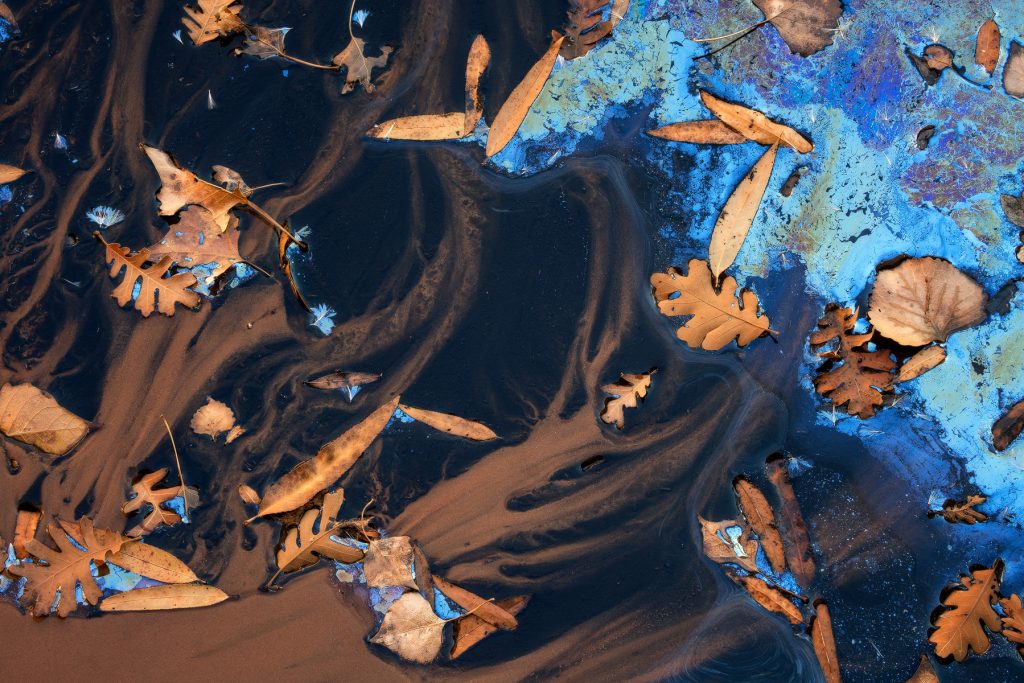

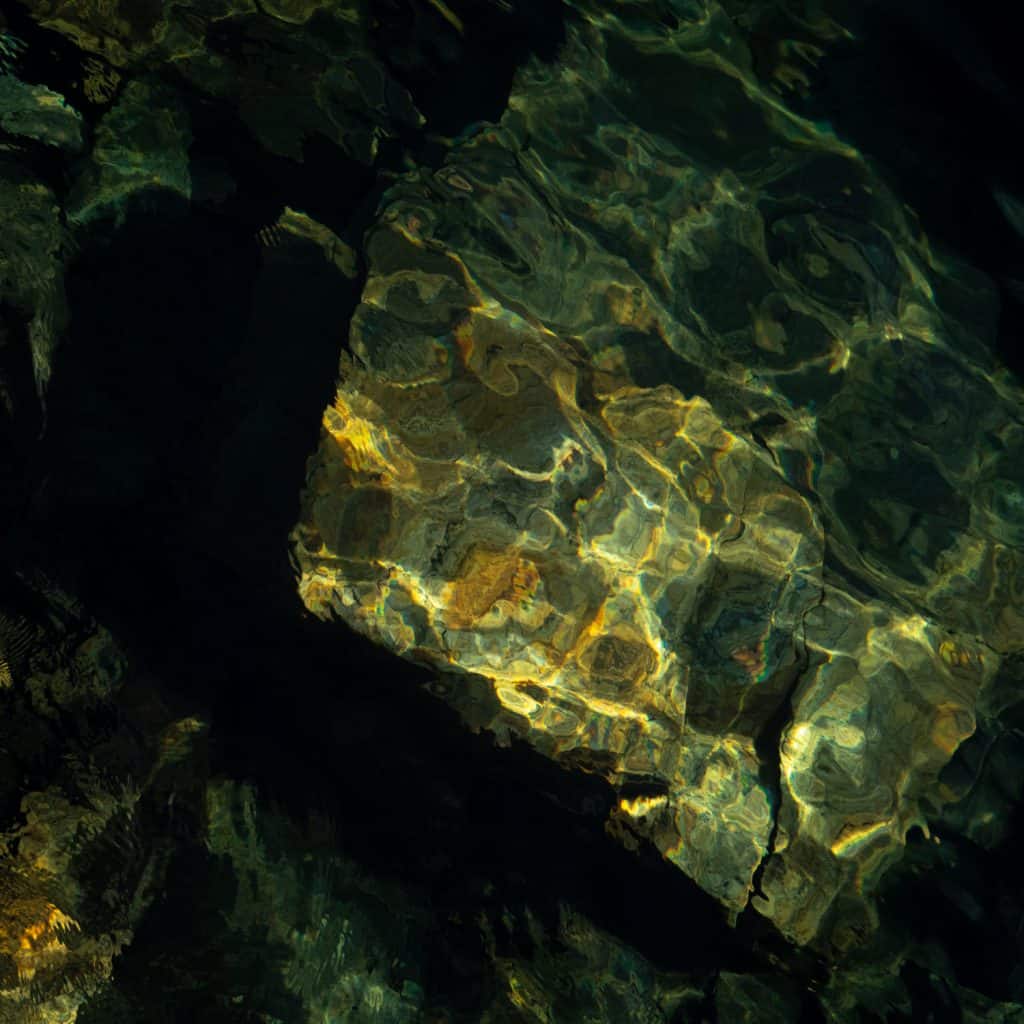

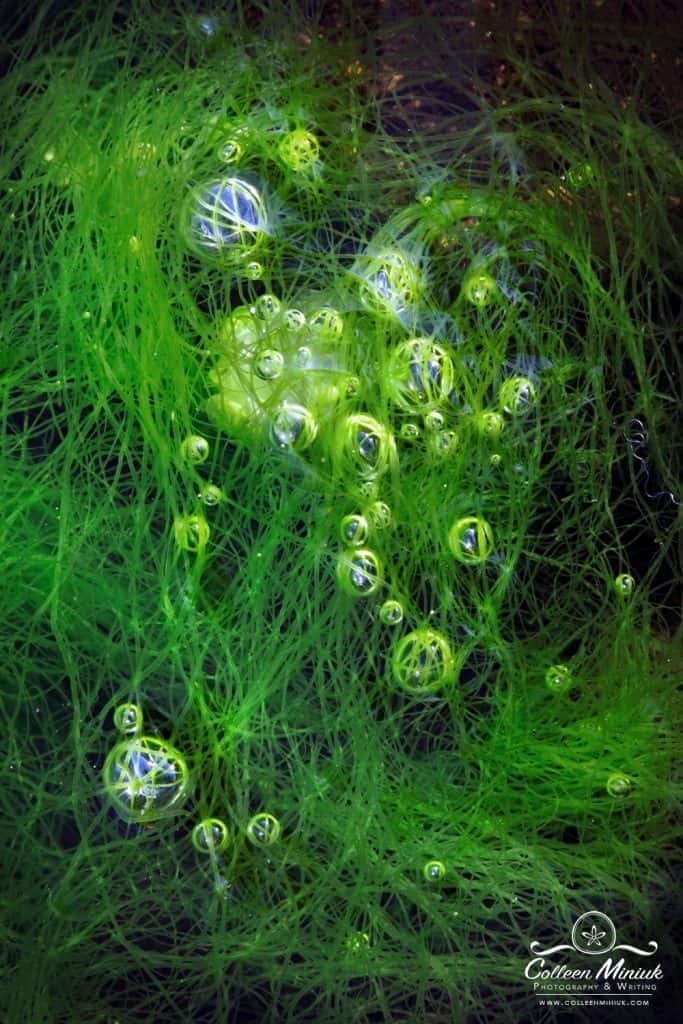

Sometimes you will find details that are better appreciated by themselves, removing all of the context of where the photo was taken, time of day, lighting, and even scale. This allows the viewer to dive deeper into the details and causes their imagination to run wild, wondering what else could be around the scene, or if it continues on forever. Including any other objects would only dilute the image and distract the viewer from focusing on the small details that you have decided are most important. The best choice is to amplify them, put them right in the viewer’s face, and not allow them to look elsewhere. Some images that come to mind are my pictures of leaves in puddles covered with biofilm. They give no suggestions to the size of the puddle, where it was shot, or during what time of day. It is also difficult to tell what focal length they were shot at, which allows the viewer to go deeper into the scene, not distracted by thoughts of a photographer taking the photo. There are certain scenarios, as a photographer, where it is of paramount importance to not betray your presence.

“Cosmic Space” GSENM, UT

“Cosmic Space” GSENM, UT

Ironically, if you think about it, the people who we usually listen to are not those that scream the loudest or that demand attention, that’s childish. The ones that talk the most are most likely to be ignored and avoided, while the ones that rarely speak and choose their words carefully are those who we are more anxious to hear from. What kind of artist do you want to be? The one that has to shout and shout, until they lose their voice? Or the one that is sought out by true admirers that are willing to devote more of their time to appreciate their work?

Visit Topic or reply to this email to respond.

To unsubscribe from these emails, click here.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

jessiemonsters

Jessie Johnson

October 10 |

Originally published at: https://naturephotographers.network/conversation-with-matt-payne/

Welcome to “In Layers”, a series of conversations that explore how the creative practices of photographers inform their images, guide their process, intersect with their personal lives and interests, and shape the landscape of nature photography as an art form.

You know those people that seem to have talent coming out of their ears? Matt Payne is one of those people. Nature photographer, avid mountaineer, father, husband, podcaster; Matt is also the program director for a local agency that serves adults with developmental disabilities.

Read on to join Matt and I as we sit down on his front porch in Durango, Colorado to discuss the evolution of his creative process, how releasing expectations has improved his craft, and how the lack of mentorship is limiting the evolution of nature photography as an art form.

Jessie: What your relationship with the creative process?

Matt Payne: To be brutally honest, it’s kind of a love-hate relationship because I’ve talked to all these amazing photographers, and they’re telling me all these amazing things that are going through their head, and I’m like, “yeah, that’s not the kind of stuff that goes through my head, what is wrong with me?” Before I started the podcast, I didn’t identify heavily with the creative process, think much about it, or even put much credence into the idea that there is a thing as a creative process. Looking back on photos that I’ve taken over the years, there was creativity involved for sure, but I don’t think it was as top of mind as it is for me now. I just have a different process, I have a different approach that I haven’t necessarily put words to, but I know for sure that I have a creative process because I know when I’m out taking photos, especially when I’m by myself, and I’m in a place I’ve never been before, my brain is going crazy. I’m taking inventory of all these visual objects and how I feel.

I’m taking inventory of a lot of things at once. Part of that might be the psychology geek in me, but having grown up in the mountains, hiking, and climbing mountains my whole life – it’s just part of my DNA. When I’m in those places, I get really excited, and then I start seeing things that I don’t necessarily think other people see as an object of creativity. I struggle a lot with naming and talking about the creative process for myself because I find the more that I’m trying, the less natural it becomes, and the output suffers. Of course, there are some exceptions of things that I come away with, and I think, “oh, I would’ve never have taken a picture like that if I wasn’t doing that.” So that’s why I say I have a love-hate relationship with it because it yields a lot of really bad results, but occasionally yields really interesting results that even surprises myself. So, I’ve struggled with the creative process a lot. What about you?

Jessie: My process of creating, whether it’s writing or photography or decorating my house, becomes better when I identify specific components that lead to the product that I was trying to create. It’s my creative process whether I put vocabulary to it or not. Sometimes that could be identifying that I work better when I eat well, or I created better photographs if I didn’t drink whiskey the night before I’m shooting, or that I am more creative if I am well-rested. The magic for me has been in identifying the things that help you flourish as a creator, in whatever medium you’re working in.

Matt Payne: Yeah, I’ve definitely noticed that my photographs tend to be better under certain conditions; both mental conditions and also environmental conditions. Not necessarily the weather, more like who I’m with or the types of conversations that I’ve had or the emotional state that I’m in because of the people that I’m with. Some of my best photography has happened when I’m with a friend of mine, Kane Engelbert. Part of that is because he sees things and shows me things that I normally wouldn’t see myself. I also think we push each other to be better. For example, last summer, we started planning a photo trip, and we wanted to go to places or shoot things that people haven’t shot before. It is kind of hard nowadays to do that well and actually come away with photos that are decent. Having somebody to think through finding those spots (Kane), is something that puts me in places where I’m going to come away with better photos. I’ve also found that I take better photos if it’s not a place that other people have shot a lot. I look at a lot of photography, but there’s danger in seeing a lot of photography because you get kind of locked into a mindset of “I have to come away with that shot,” and I think that can be a hard trap to pull yourself out of if you’re in a place like that. I find that if I purposely put myself in places that I haven’t seen photos of before, my photos are going to be better by the nature of having to think through it myself. Maybe that’s a creative process, I don’t know.

Jessie: It sounds like you do a lot of lead up work to create unique photographs.

Matt Payne: Sometimes. And sometimes it’s just wandering around in the forest and seeing something that catches your attention. Sometimes it’s that simple. Why did it catch your attention but not to the 20 other people that looked before you? I think that’s one of the exciting things about landscape photography is that you can take 20 landscape photographers, walk the same trail, and people are going to come away with 20 different types of photos, which is really cool. Each person has their own creative process that’s driving that. A lot of people are probably like me in that they don’t necessarily have a way of talking about what that process is. It’s hard for me to talk about the creative process, I know I have one, but I don’t know if I could teach it. I would have to teach you how to appreciate and love the things that I love because that’s a huge part of my creative process. I see things that really interest me and that I’m curious about, which may bore somebody else. It’s different for everybody, everyone has a different process. My process is certainly going to be a lot different than Sarah Marino’s. I went on a shooting with Ron Coscorossa, Sarah Marino, Jennifer Renwick, Alex Noriega, and David Kingham last year, and watching all of them was really interesting. They are very different process and all of those processes are way different than mine. They’re showing me stuff that’s interesting to them, and I don’t see it. I see something else way over there that I think is cool looking.

Jessie: In those situations, would you say that your own identity is interfacing with the environment in a way that attracts you to certain images and not others?